Indeed, given the trajectories of the current phase of institutional and governance reform that commenced in 1999 and reached a defining height in 2003, several cogent questions became imperative as the key to determining the direction the Nigerian public service system was heading. These questions include:

What kind of public service Nigeria needs to successfully manage the transition from military authoritarianism to democratic governance; and

What are the appropriate personnel policies, pay structure, and operational cost ratios that are most cost effective will be, to achieve optimal productivity level in the national economy.

Unfortunately, and more than twenty-five years later, it would seem that for Nigeria, to quote the French critic and journalist, Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr, “the more things change, the more they stay the same.”

This brief diagnostic analysis brings me to the challenge of the unfinished business of institutional reform that will task the collaborative partnership between CIPM, and the public administration community of service and practice with regard to the core elements of transforming the public service systems.

Transforming the public service requires paying attention to workplace dynamics that have been subjected to myriads of changes, especially those that relate to the nature and frameworks of work itself. Given the changing demographics of employees and workers, the workplace now demands new orientations and innovation — like flexi-working — that take into consideration the new normal after the COVID-19 pandemic and the emergence of the Gen Z demographic. Such orientations demand the urgency of rethinking HR functions from multiple perspectives.

This is even made more cogent by the fact that government has gradually ceased to be the employer of choice for most people given its lack of incentivisation for working in the public service. To change this condition, and key into the unfinished business of reforming the public service, several issues come to the fore.

One, since the HR function is cogent in achieving performance and productivity, there is no doubt that the professionalisation of the HR functions is fundamental to transforming the workplace. However, the core professionals need to know that to do this, human resource management can no longer be restricted as the exclusive responsibility of HR departments.

Line managers and other managerial executives now require people management skills and competence to facilitate effectiveness and efficiency. This also relocates the HR function from the back to the front office. And rethinking the HR function implies a significant level of reform.

For instance, at the basic level, it is no longer productive to treat HR in terms of personnel management, and its preoccupation with the passive role of privileging rules, regulations and procedures rather than developing and pursuing policies in manners that extract performance results and productivity bargains from people and from the processes.

This automatically affects the current practice of staff performance appraisal which is very vague about what is being assessed and rewarded, or even how appraisal should be directed towards performance assessment and competences, rather than as a mere subjective protocol.

Two, it has become almost impossible to think of public service transformation without inserting such reform within the public-private partnership (PPP) framework. Working within this framework demands optimising the PPP contracts through imbuing public officials with commercial skills and competences that open up their capacities to engage with clients, customers and citizens, acquire knowledge of international business practices and labour laws, adopt multicultural sensitivities and multiple languages, and so on.

This also brings in the growing consequences of involving artificial intelligences and robotics in upscaling the performance and efficiency of the public service system. The real challenge is how to translate the uncertainties that attend the deployment of artificial intelligence at the moment to real opportunities that will impact the public service system.

Three, to become the ultimate change agents in the reform of the public service, the HR manager is not only expected to facilitate the establishment of a new HR model that will harness the performance and productive capacities of the workforce. They are also essentially required to deepen the skills and competences with regard to risk management in ways that instigate action research as a component of management cum operation research and organisation development (OD) in the MDAs.

This will also enable the HR to institute a learning culture that challenges the bureaucratic status quo, and helps it champion specific cultural transformations directed at translating desirable culture and public service values into public managers behaviour.

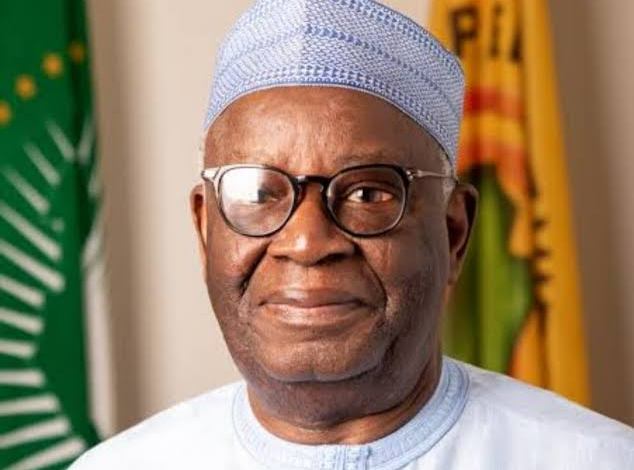

The CIPM is strategically located as a key stakeholder in injecting its organisational strengths into articulating a significant blueprint that inserts the organisation into a collaborative partnership needed to keep afloat the business of reforming the public service system. I have no iota of doubt that the new chairman will not only build on the existing architecture of achievements of the previous chairpersons, but also lay a few solid foundations of his that will keep the CIPM on course as a change agent in Nigeria’s effort to build a world class public service that backstops her democratic governance.

Concluded.

Olaopa, a Professor of Public Administration and the Chairman, Federal Civil Service Commission, Abuja, gave this address as the Chairman of the Investiture ceremony recently.

3 months ago

4

3 months ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·