Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is a global mandate aimed at ensuring that everyone, everywhere can access quality health services without suffering financial hardship.

It is a cornerstone of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 3.8, which reads, “Achieve UHC, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all.”

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), UHC covers the full continuum of essential health services, from health promotion to prevention, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care.

However, with only six years left until the 2030 target, Nigeria, Africa’s most populous nation, faces mounting pressure to fulfil its UHC commitment.

While significant strides have been made through policy reforms like the National Health Insurance Authority Act (NHIA 2022) and the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF), millions of Nigerians still grapple with inequitable access to healthcare.

As the world marked UHC Day on 12 December with the theme “Health: It’s on the Government,” PREMIUM TIMES examines Nigeria’s journey so far, challenges, and prospects for achieving UHC by 2030.

NHIA, a major step

As part of efforts to ensure health coverage for all, former President Muhammadu Buhari signed into law the National Health Insurance Authority Bill 2022 on 19 May 2022. The new law replaces the National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) Act, which existed for about 18 years with no significant impact.

Nigerians need credible journalism. Help us report it.

Support journalism driven by facts, created by Nigerians for Nigerians. Our thorough, researched reporting relies on the support of readers like you.

Help us maintain free and accessible news for all with a small donation.

Every contribution guarantees that we can keep delivering important stories —no paywalls, just quality journalism.

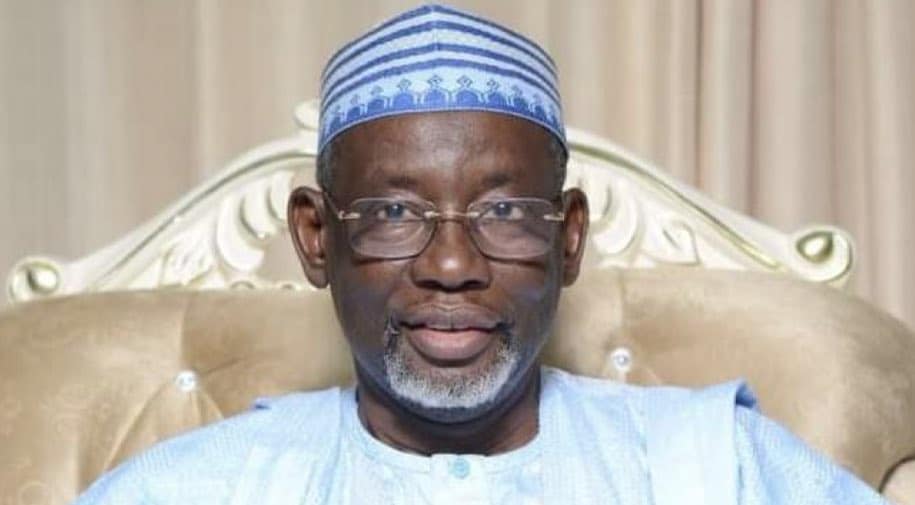

Former Nigerian President, Muhammadu Buhari

Former Nigerian President, Muhammadu BuhariThe NHIA makes health insurance mandatory for all citizens and legal residents and creates a mechanism to finance health service delivery for the poor and vulnerable.

It is one mechanism for providing financial protection from the costs of healthcare services, a key pillar of achieving UHC. This is especially important as research from the World Bank and the WHO indicates that more than half a billion people are pushed into extreme poverty annually due to healthcare expenses.

Despite this, according to a 2024 survey by NOI Polls, only about 19 in 100 Nigerians have health insurance coverage in Africa’s most populous country.

Also, according to the World Bank, Nigeria’s out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure stood at over 76 per cent in 2021.

Although most Nigerians are yet to be covered by health insurance, the Director-General of NHIA, Kelechi Ohiri, said the country has recorded significant progress in recent years.

Mr Ohiri, at a press briefing to commemorate the 2024 UHC Day, said before the enactment of the NHIA in 2022, Nigeria’s health insurance coverage stagnated at approximately seven per cent for nearly two decades.

He said this was largely due to the limited scope of health insurance, which predominantly served the formal sector, leaving the poor and vulnerable underserved.

However, he said health insurance coverage has increased from 16.7 million to 19.2 million Nigerians – a 14 per cent growth in about a year.

“The NHIA now aims to address existing gaps by enforcing mandatory health insurance, increasing public awareness, and restoring trust in the system,” he said.

Bolanle Faleye, chief of party for the USAID Local Health System Sustainability (LHSS) project, acknowledged the progress made through UHC initiatives but emphasised persistent gaps in financial risk protection, equitable healthcare delivery, and access to essential services.

Mrs Falaye highlighted the burden of out-of-pocket payments, which she said should ideally be reduced to no more than 30 per cent of total healthcare spending.

“Out-of-pocket expenses, a key barrier to UHC, remain as high as 76 per cent. This places a significant financial burden on individuals during vulnerable moments,” she said.

She stressed the need to significantly boost health insurance enrolment to meet the 2030 UHC target, emphasising that only about 19 million people are covered under health insurance nationwide – a far cry from the target.

Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF)

Established in 2014 under Section 11 of the National Health Act, the BHCPF provides funding to enhance access to primary health care, a critical step towards advancing the country’s progress towards UHC.

It was designed to be financed from at least one per cent of the federal government’s Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) and other sources, including donors’ contributions.

The Fund provides a Basic Minimum Package of Health Services (BMPHS) aimed at increasing the fiscal space for health, strengthening the national health system, particularly at the PHC level, and ensuring access to healthcare for all.

Although the BHCPF was established in 2014, funding was not allocated for its implementation until 2018. Since then, over 8,000 primary healthcare centres (PHCs) across the country have benefited from the fund, according to the Coordinating Minister of Health and Social Welfare, Muhammad Pate.

Professor Muhammad Ali Pate

Professor Muhammad Ali PateIn December last year, Mr Pate said the BHCPF would receive at least $2.5 billion in pooled and non-pooled financing from 2024 to 2026 to improve the primary health system nationwide.

During the ministerial sectoral briefing in May, Mr Pate said N260 billion has been set aside to revitalise PHCs nationwide.

Also, in November, he said N45 billion had already been disbursed through direct facilities to the state and to serve the country’s population.

“Under the PHC 2.0 reform, we have emphasised equity by allocating financial and human resources across over 8,000 primary healthcare centres. Direct facility disbursements totalling N45 billion have been sent to states, reaching our people directly,” he said.

Despite these efforts, challenges persist in implementing and managing the BHCPF. Delayed disbursements, weak accountability mechanisms, and disparities in fund utilisation have limited its effectiveness.

Many PHCs nationwide still lack essential equipment, medicines, and trained personnel, making it difficult for them to meet their communities’ demands.

Nigeria Health Sector Renewal Investment Initiative (NHSRII)

One year ago, President Bola Tinubu unveiled the Nigeria Health Sector Renewal Investment Initiative (NHSRII) to drive Nigeria towards achieving UHC by 2030.

The initiative aims to improve population health outcomes through the primary healthcare system and enhance the country’s reproductive, maternal, and child health services.

At the unveiling, Mr Pate said the quest to achieve UHC and better health for Nigerians requires a multi-sectoral and whole-of-government approach.

He said the initiative will leverage the BHCPF, in partnership with state governments and development partners, in a transformational Sector-Wide Approach (SWAp) to improve health outcomes. The idea is to align resources with national health priorities, reduce duplication of efforts, and foster accountability.

Health experts are optimistic that the approach, focusing on collaboration and coordination, will significantly impact the country’s health outcomes.

The Executive Director of the Vaccine Network for Disease Control (VNDC), Chika Offor, said the sector-wide approach is commendable because the government cannot achieve these health objectives alone.

Ms Offor said all sectors, including the private sector, must fully engage in the process.

Health sector funding

Nigeria’s health sector has long struggled with underfunding, which remains a critical barrier to achieving UHC and improving overall health outcomes.

In 2001, African Union (AU) member countries, including Nigeria, committed to allocating at least 15 per cent of their national budgets to healthcare under the Abuja Declaration. However, Nigeria has consistently fallen short of this target over the past two decades.

A review of the budgetary allocation to the health sector in the last 22 years revealed that Nigeria has consistently fallen below the 15 per cent benchmark. In 2024, despite expectations for a shift in funding priorities under President Tinubu’s administration, the health sector received just over five per cent of the national budget.

President Bola Tinubu (PHOTO CREDIT: Presidency)

President Bola Tinubu (PHOTO CREDIT: Presidency)The low allocation to the sector has led to inadequate healthcare facilities, delays in implementing health programmes, and persistent gaps in essential services, particularly in rural areas.

Ms Offor said the health sector is underfunded, which is why it is underperforming. She noted that the majority of children are still unimmunised because of a lack of adequate funding in the health system.

“As Nigeria approaches the 2030 UHC target, this shortfall in funding continues to undermine efforts to improve life expectancy, reduce maternal and infant mortality rates, and strengthen the nation’s overall health infrastructure,” she said.

Workforce crisis, brain drain

One of the most pressing challenges facing Nigeria’s health sector is the ongoing workforce crisis. A critical shortage of skilled healthcare professionals, particularly doctors and nurses, has undermined efforts to achieve UHC and deliver quality care nationwide.

The crisis is particularly severe in rural and remote areas, where healthcare professionals are unwilling or unable to work due to poor infrastructure, inadequate compensation, and limited professional development opportunities.

As a result, many rural communities remain underserved, with little or no access to essential health services such as maternal and child care, treatment for infectious diseases, and chronic disease management.

In addition to these geographical disparities, Nigeria has been grappling with an increasing exodus of healthcare professionals, especially doctors, pharmacists, and nurses, to developed countries. According to recent reports, thousands of healthcare professionals leave Nigeria annually to seek better opportunities abroad.

In March, Mr Pate disclosed that about 16,000 doctors had left the country in the last five years, noting that Nigeria now has only 55,000 licensed doctors to serve its growing population of over 200 million.

The mass exodus of skilled healthcare professionals, which has further strained the country’s healthcare system, is driven by poor working conditions, low salaries, limited career advancement, and insecurity.

According to Mohammad Mohammad, president of the Medical and Dental Consultants Association of Nigeria (MDCAN), fewer than 10 per cent of PHCs have doctors, and specialist shortages at primary and secondary healthcare levels intensify the crisis.

Mr Mohammad, a surgeon, stressed the need for deliberate strategies to retain healthcare workers and incentivise rural postings.

“Out of the 110,000 registered doctors inducted by MDCN, only about 40,000 remain in Nigeria. This uneven distribution increases workloads, leading to burnout and compromising the quality of care.”

Dependence on donor funding

Nigeria’s health sector has historically relied heavily on donor funding to sustain many programmes. Contributions from international organisations like the Global Fund, Gavi, and USAID have played a vital role in addressing the country’s pressing health needs.

These funds support a significant portion of immunisation initiatives, ensuring millions of children receive life-saving vaccines, and contribute extensively to HIV/AIDS programmes, among other health interventions.

While donor contributions have been instrumental, this heavy reliance poses significant risks to the sustainability of Nigeria’s health system. Unpredictable funding flows – often influenced by global economic challenges and shifting health priorities in donor countries – can result in abrupt programme disruptions.

For instance, in 2021, the United Kingdom announced it would withdraw its annual £3 million from the basket fund for Family Planning (FP) commodities in Nigeria. This decision left the Nigerian government scrambling to bridge the funding gap, which jeopardised women’s access to essential contraceptives.

Such reliance also limits domestic ownership, making it challenging for Nigeria to establish and sustain locally driven health initiatives.

Health experts believe that achieving UHC by 2030 requires Nigeria to take the lead in financing its health system.

The Executive Director of VNDC, Ms Offor, stressed the importance of transitioning from donor-dependent programmes to sustainable, locally financed initiatives.

“By taking the lead in financing its health system, Nigeria would have greater control over its health priorities and resource allocation,” she said.

She said overcoming this dependency will necessitate increased investment in the health sector, strategic partnerships with the private sector, and sustainable funding mechanisms to ensure continuity and resilience in healthcare delivery.

She added that this shift is essential for achieving UHC, strengthening Nigeria’s health sovereignty and ensuring long-term health outcomes are not at the mercy of external decisions.

Support PREMIUM TIMES' journalism of integrity and credibility

At Premium Times, we firmly believe in the importance of high-quality journalism. Recognizing that not everyone can afford costly news subscriptions, we are dedicated to delivering meticulously researched, fact-checked news that remains freely accessible to all.

Whether you turn to Premium Times for daily updates, in-depth investigations into pressing national issues, or entertaining trending stories, we value your readership.

It’s essential to acknowledge that news production incurs expenses, and we take pride in never placing our stories behind a prohibitive paywall.

Would you consider supporting us with a modest contribution on a monthly basis to help maintain our commitment to free, accessible news?

TEXT AD: Call Willie - +2348098788999

English (US) ·

English (US) ·