BBC

BBC

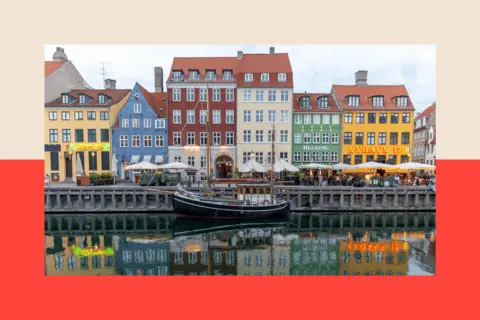

Think, Denmark. Images of sleek, impossibly chic Copenhagen, the capital, might spring to mind. As well as a sense of a liberal, open society. That is the Scandinavian cliché.

But when it comes to migration, Denmark has taken a dramatically different turn. The country is now "a pioneer in restrictive migration policies" in Europe, according to Marie Sandberg, Director of the Centre for Advanced Migration Studies (AMIS) at the University of Copenhagen - both when it comes to asylum-seekers and economic migrants looking to work in Denmark.

Even more surprising, perhaps, is who is behind this drive. It's generally assumed 'far right' politicians are gaining in strength across Europe on the back of migration fears, but that's far from the full picture.

In Denmark – and in Spain, which is tackling the issue in a very different but no less radical way by pushing for more, not less immigration - the politicians taking the migration bull by the horns, now come from the centre left of politics.

How come? And can the rest of Europe - including the UK's Labour government - learn from them?

Unsettling times in Europe

Migration is a top voter priority, right across Europe. We live in really unsettling times. As war rages in Ukraine, Russia is waging hybrid warfare, such as cyber attacks across much of the continent. Governments talk about spending more on defence, while most European economies are spluttering. Voters worry about the cost of living and into this maelstrom of anxieties comes concern about migration.

But in Denmark, the issue has run deeper, and for longer.

Immigration began to grow apace following World War Two, increasing further – and rapidly - in recent decades. The proportion of Danish residents who are immigrants, or who have two immigrant parents, has increased more than fivefold since 1985, according to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI).

A turning point was ten years ago, during the 2015 European migration and refugee crisis, when well over a million migrants came to Europe, mostly heading to the wealthier north, to countries like Denmark, Sweden and Germany.

Athanasios Gioumpasis / Getty

Athanasios Gioumpasis / Getty

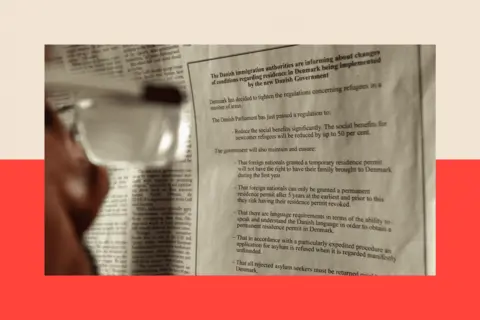

Denmark allowed authorities to confiscate asylum seekers' jewellery and valuables

Slogans like "Danskerne Først" (Danes First) resonated with the electorate. When I interviewed supporters of the hard-right nationalist, anti-immigration, Danish People's Party (DPP) that year they told me, "We don't see ourselves as racists but we do feel we are losing our country."

Denmark came under glaring international attention for its hardline refugee stance, after it allowed the authorities to confiscate asylum seekers' jewellery and other valuables, saying this was to pay towards their stay in Denmark.

The Danish immigration minister put up a photo of herself on Facebook having a cake decorated with the number 50 and a Danish flag to celebrate passing her 50th amendment to tighten immigration controls.

And Danish law has only tightened further since then.

Plans to detain migrants on an island

Mayors from towns outside Copenhagen had long been sounding the alarm about the effects of the speedy influx of migrants.

Migrant workers and their families had tended to move just outside the capital, to avoid high living costs. Denmark's famous welfare system was perceived to be under strain. Infant schools were said to be full of children who didn't speak Danish. Some unemployed migrants reportedly received resettlement payments that made their welfare benefits larger than those of unemployed Danes, and government statistics suggested immigrants were committing more crimes than others. Local resentment was growing, mayors warned.

Today Denmark's has become one of the loudest voices in Europe calling for asylum seekers and other migrants turning up without legal papers to be processed outside the continent.

The country had first looked at detaining migrants without papers on a Danish island that used to house a centre for contagious animals. That plan was shelved.

Then Copenhagen passed a law in 2021 allowing asylum claims to be processed and refugees to be resettled in partner countries, like Rwanda. The UK's former Conservative government attempted a not dissimilar plan that was later annulled.

Copenhagen's Kigali plan hasn't progressed much either but it's tightened rules on family reunions, which not long ago, was seen as a refugee's right. It has also made all refugees' stay in Denmark temporary by law, whatever their need for protection.

But many of Denmark's harsh measures seemed targeted as much at making headlines, as taking action. The Danish authorities intentionally created a "hostile environment" for migrants", says Alberto Horst Neidhardt, senior analyst at the European Policy Centre.

And Denmark has been keen for the word to spread.

AFP via Getty

AFP via Getty

Denmark placed adverts in Lebanese newspapers warning how tough Danish migration policies were

It put advertisements in Lebanese newspapers at the height of the migrant crisis, for example, warning how tough Danish migration policies were.

"The goal has been to reduce all incentives to come to Denmark," says Susi Dennison, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

"The Danes have gone further than most European governments," she explains. Not just honing in on politically sensitive issues like crime and access to benefits but with explicit talk about a zero asylum seekers policy.

And yet "before the 2015 refugee crisis, there was a stereotype of Nordic countries being very internationalist… and having a welcoming culture for asylum seekers," says Ms Dennison.

Then suddenly the reaction was, "No. Our first goal is to provide responsibly for Danish people."

The turning-point was, she argues, also triggered by Denmark's neighbour, Germany, allowing a million refugees and others to stay in the country, during the migrant crisis.

"That was a political choice that had repercussions across Europe."

Where Denmark's left came in

By 2015 the anti-migration Danish People's Party was the second biggest power in Denmark's parliament. But at the same time, the Social Democrats - under new leader Mette Frederiksen – decided to fight back, making a clear, public break with the party's past reputation of openness to migration.

"My party should have listened," Frederiksen said.

Under her leadership, the party tacked towards what's generally seen as the political "far right" in terms of migration and made hardline DPP-associated asylum policies, their own. But they also doubled down on issues more traditionally associated with the left: public services.

Danes pay the highest tax rates in Europe across all household types. They expect top notch public services in return. Frederiksen argued that migration levels threatened social cohesion and social welfare, with the poorest Danes losing out the most.

That is how her party justify their tough migration rules.

Anadolu via Getty

Anadolu via Getty

Many refugees stayed in Germany during the migrant crisis in 2015

Frederiksen's critics see her 'rightwards swing' as a cynical ploy to get into, and then stay in, power. She insists her party's convictions are sincere. Whatever the case, it worked in winning votes.

Federiksen has been Denmark's prime minister since 2019, and in last year's election to the European Parliament, the populist nationalist Danish People's Party scrambled to hold on to a single seat.

A blurring of left and right?

The political labels of old are blurring. It's not just Denmark. Across Europe, parties of the centre - right and left - are increasingly using language traditionally associated with the "far right" when it comes to migration to claw back, or hold on to votes.

Sir Keir Starmer recently came under fire when, during a speech on immigration, he spoke of the danger of his country becoming 'an island of strangers'.

At the same time in Europe, right-wing parties are adopting social policies traditionally linked to the left to broaden their appeal.

Carl Court / Getty

Carl Court / Getty

Recent UK governments have focused on high profile issues like people smugglers' boats crossing the Channel

In the UK, the leader of the anti-migration, opposition Reform Party Nigel Farage has been under attack for generous shadow budget proposals that critics say don't add up.

In France, centrist Emmanuel Macron has sounded increasingly hardline on immigration in recent years, while his political nemesis the National Rally Party leader Marine Le Pen has been heavily mixing social welfare policies into her nationalist agenda to attract more mainstream voters.

Avoiding 'hysterical rhetoric'

But can Danish - and in particular, Danish Social Democrat - tough immigration policies be deemed a success?

The answer depends on which criteria you use to judge them.

Asylum claim applications are certainly down in Denmark, in stark contrast to much of the rest of Europe. The number, as of May 2025, is the lowest in 40 years, according to immigration.dk, an online information site for refugees in Denmark.

But Nordic Denmark is certainly not what's seen as a frontline state - like Italy - where people smugglers' boats frequently wash up along its shores.

"Frederiksen is in a favourable geographical position," argues Europe professor, Timothy Garton Ash, from Oxford University. But he also praises Denmark's prime minister for addressing the problem of migration, without adopting "hysterical rhetoric".

EPA - EFE/Shutterstock

EPA - EFE/Shutterstock

Mette Frederiksen has been Danish prime minister since 2019

But others say new legislation has damaged Denmark's reputation for respecting international humanitarian law and the rights of asylum-seekers. Michelle Pace of Chatham House says it has become hard to protect refugees in Denmark, where "the legal goalposts keep moving."

Danish citizens with a migrant background have also been made to feel like outsiders, she notes.

She cites the Social Democrats' "parallel societies" law, which allows the state to sell off or demolish apartment blocks in troubled areas where at least half of residents have a "non-Western" background.

The Social Democrats say the law is aimed at improving integration but Ms Pace insists it is alienating. The children of immigrants are told they aren't Danish or a "pure Dane," she argues.

In February this year, a senior advisor to the EU's top court described the non-Western provision of the Danish law as discriminatory on the basis of ethnic origin.

Whereas once a number of European leaders dismissed Denmark's Social Democrats as becoming far right, now "the Danish position has become the new normal - it was the head of the curve," says Alberto Horst Neidhardt.

"What's considered 'good' migration policies these days has moved to the right, even for centre left governments, like the UK."

Before Germany's general election this year, then centre-left Chancellor, Olaf Scholz, pledged to tighten asylum regulations, including reducing family reunification.

And earlier this month, Frederiksen teamed up with eight other European leaders - not including the UK - to call for a reinterpretation of the European Convention on Human Rights, whose tight constraints, they claim, prevent them from expelling foreign nationals with criminal records.

Contesting international laws on asylum is a trend Denmark is establishing at a more European level, says Sarah Wolff, Professor of International Studies and Global Politics at Leiden University.

"With the topic of migration now politicised, you increasingly see supposedly liberal countries that are signatories to international conventions, like human rights law, coming back on those conventions because the legislation no longer fits the political agenda of the moment," says Ms Wolff.

Despite the restrictive migrant legislation, Denmark has continued to admit migrant workers through legal channels. But not enough, considering the rapidly aging population, say critics like Michelle Pace.

She predicts Denmark will face a serious labour shortage in the future.

The other extreme: Spain's model

Spain's centre-left government, meanwhile, is taking a very different road. Its Social Democrat prime minister, Pedro Sanchez, loves pointing out the Spanish economy was the fastest growing amongst rich nations last year.

Its 3.2% GDP growth was higher than America's, three times the UK's and four times the EU average.

Sanchez wants to legalise nearly a million migrants, already working in Spain but currently without legal papers. That extra tax revenue plus the much-needed extra workers to plug gaps in the labour market will maintain economic growth and ensure future pension payments are covered, he says.

Spain has one of the lowest birth rates in the EU. Spanish society is getting old, fast.

"Almost half of our towns are at risk of depopulation," he said in autumn 2024. "We have elderly people who need a caregiver, companies looking for programmers, technicians and bricklayers... The key to migration is in managing it well."

Critics accuse Sanchez of encouraging illegal migration to Spain, and question the country's record of integrating migrants. Opinion polls show that Sanchez is taking a gamble: 57% of Spaniards say there are already too many migrants in the country, according to public pollster 40dB.

In less than 30 years, the number of foreign-born inhabitants in Spain has jumped almost nine fold from 1.6% to 14% of the population. But so far, migration concerns haven't translated into widespread support for the immigration sceptic nationalist Vox party.

The Sanchez government is setting up what Ms Pace calls a "national dialogue", involving NGOs and private business. The aim is to balance plugging labour market gaps with avoiding strains on public services, by using extra tax revenue from new migrant workers, to build housing and extra classrooms, for example.

Right now the plan is aspirational. It's too early to judge, if successful, or not.

So, who's got it right?

"Successful" migration policy depends on what governments, regardless of their political stripe, set as their priority, says Ms Dennison.

In Denmark, the first priority is preserving the Danish social system. Italy prioritises offshoring the processing of migrants. While Hungary's prime minister Victor Orban wants strict migrant limits to protect Europe's "Christian roots", he claims.

Overstaying visas is thought to be the most common way migrants enter and stay in Europe without legal papers.

But recent UK governments have focused on high profile issues like people smugglers' boats crossing the Channel.

Ms Dennison thinks that's a tactical move. It's taking aim at visible challenges, to "neutralise public anger" she says, in the hope most voters will then support offering asylum to those who need it, and allow some foreign workers into the UK.

EPA - EFE/Shutterstock

EPA - EFE/Shutterstock

It would be hard for Starmer to pursue the Denmark approach, argues one expert

It would be hard for Starmer to pursue the Denmark approach, she adds. After taking over from previous Conservative governments, he made a point of recommitting the UK to international institutions and international law.

So, does the 'ideal' migration plan exist, that balances voter concerns, economic needs and humanitarian values?

Martin Ruhs, deputy director of the Migration Policy Centre, spends a lot of time asking this question to voters across the UK and the rest of Europe, and thinks the public is often more sophisticated than their politicians.

Most prefer a balance, he says: migration limits to protect themselves and their families, but once they feel that's in place, they also favour fair legislation to protect refugees and foreign workers.

Top picture credit: SOPA Images via Getty

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

1 day ago

4

1 day ago

4

English (US) ·

English (US) ·