For two years, the implementation of the National Language Policy, which allows the use of mother tongue to teach children up to primary six, has dragged on, disrupting learning and putting pupils at the receiving end, IYABO LAWAL reports.

In November 2022, the then Minister of Education, Prof. Adamu Adamu, announced that the Federal Executive Council (FEC) had approved a National Language Policy for primary schools nationwide.

Adamu had revealed that the mother tongue would be used exclusively for the first six years of education, while it would be combined with English Language from Junior Secondary School.

While many applauded the move, saying it would save the already dying mother tongue across all generations, there were, however, questions about the policy’s feasibility and implementation. and a growing concern about children, who are in school but not learning, especially those in rural communities.

A report by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) noted that three out of four children aged between six and 14 in Nigeria cannot read a text with understanding, or solve simple mathematical problems.

Unfortunately, there is a limited chance to catch up later. A situation where 69 per cent of primary school teachers in the country are said to be unqualified to impart basic foundational skills to children has continued to worsen the situation.

The World Bank, in a recent report about Nigeria’s standard of education, also stated that the country is experiencing a learning poverty, where 70 per cent of 10-year-olds cannot understand a simple sentence or perform basic numeracy tasks.

Poor funding of the sector tops the list of factors responsible for low learning outcomes and poor numeracy skills in children.

Research showed that many enrolled children lose interest, become absent-minded, appear lost and generally avoid school when tutored in languages other than a familiar tongue.

Children who manage to sit through classes are often said to have a very faint grasp of subjects taught or mix up knowledge because of poor understanding.

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) has tested teaching initiatives to promote mother language-based education in Djibouti, Gabon, Guinea, Haiti and Kenya with success.

Also, countries like China, Japan, Taiwan, and South Africa that use mother tongue to teach science and technology are higher on the United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) than Nigeria and others that use foreign languages.

The late Prof. Babatunde Fafunwa, former Minister of Education and first Nigerian professor in education, had conducted a research where he discovered that teaching and learning in mother tongue was highly effective, and the best language mechanism in impacting knowledge, especially in the early stages of life.

He said the research was able to prove that “language is an important vehicle of disseminating information and imparting knowledge.

“Mother-tongue is the easiest and most accessible medium of teaching that facilitates quick understanding, comprehension and responses.”

Experts react

Wondering why government has failed to implement the language policy almost two years after,stakeholders argued that teaching in mother tongue at basic education level would improve the literacy and numeracy of pupils.

They maintained that adoption of foreign languages in Nigeria school system, especially in basic education, did more harm than good. They said the negative impact could be seen in the field of science and technology, and other fields, hence, the strong campaign for the formal adoption of mother language in schools for effective results.

Chief of Education at UNICEF Nigeria, Saadhna Panday-Soobrayan said

when children are taught in their mother tongue, especially at age one to three, they learn better and faster.

She noted that the use of mother tongue assists the children to acquire basic numeracy and literacy skills, subsequently leading to improved results.

“In addition, teachers should be trained to teach in local languages. There should also be books and other tutorial materials produced in local languages. These would also go a long way in solving the literacy problems in Nigeria,” she stated.

Executive Secretary, Nigeria Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC), Prof. Ismail Junaidu, identified lack of political will, shortage of language teachers, low capacity and inadequate funds to implement the policy as some of the challenges hindering the implementation.

He called on relevant bodies to intensify sensitisation, produce more instructional materials, build capacity of teachers and ensure partnership between agencies and development partners for proper implementation of the policy.

Executive Director, Education for all initiative, Toyin Olopade, said the use of learners’ own languages for literacy and learning provides a solid pillar for education, and for transfer of skills and knowledge to additional languages.

Olopade added that learning in one’s first language facilitates understanding and interaction, and further develops critical thinking.

“In addition to boosting learning, multilingual education contributes to opening the doors to intergenerational learning, the preservation of culture and intangible heritage, and the revitalisation of languages,” she stated.

The Federal Engagement Lead on the Partnership for Learning for All in Nigeria (PLANE) programme, Abiola Sanusi noted that education in the mother tongue helps children develop a strong foundation in their native language.

According to Sanusi, to fully realise the benefits of education in the mother tongue, it is essential for policymakers and educators to recognise the importance of language as a tool for learning and development.

He explained that education in the mother tongue helps children develop a strong foundation in their native language, which is important for their overall cognitive development, as well as their emotional and social well-being.

“When children are educated in their mother tongue, they are better able to express themselves, ask questions, and engage in meaningful discussions with their teachers and peers. This leads to a more stimulating and inclusive learning environment and alignment with foundational principles of starting from known to unknown in learning process,” Sanusi said.

He, however, noted that encouraging the use of the mother tongue does not negate the importance of the English Language in creating a connection with the rest of the global community.

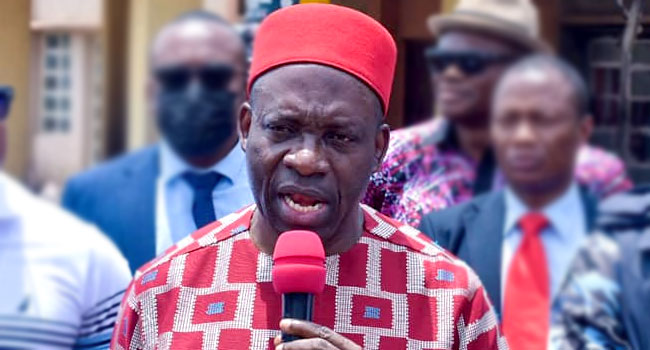

The Executive Secretary, Universal Basic Education Commission (UBEC), Hamid Bobboyi, warned that Nigeria may not achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), specifically, goal four, which deals with inclusive and equitable quality education and promotion of lifelong learning opportunities for all, if the learning crisis is not immediately addressed.

On her part, a retired principal, Mrs Tomilola Ogunsola, pointed out that education in the mother tongue will help children develop a strong foundation in their native language.

According to her, when individuals are proficient in multiple languages, they develop the ability to navigate different linguistic and cultural schemes, expanding their capacity for empathy and understanding.

Others added that the policy would help pupils learn more effectively and efficiently, with the learner likely to retain what he or she has been taught for use in the future.

Opposition to the policy

However, a Professor of Account Management, Crawford University, Igbesa, Ogun State, Comfort Omorogbe, objected to the use of mother tongue in schools.

Despite the three main languages, she noted that students, who go through language classes in schools, still cannot communicate with it effectively.

In an ever-evolving society where development and technology is advancing, Omorogbe noted that learning in native language would keep the country perpetually backward.

In the same vein, a school owner, Mrs Lola Olakojo, said pupils who transferred from another area or state would face communication challenges and lack of reading materials.

“If the teacher is not conversant with the language, pupils will lose out academically, while some will equally face pronunciation challenges of some words.”

Others also described the approval for the use of mother tongue in elementary schools across the nation as a setback to the nation’s already comatose education sector.

For instance, Dr Olu Adeojo, a public analyst, said though English is the official language, many Nigerians are still battling with poor communication techniques.

He lamented that majority of Nigerians, including pupils, students, and even university graduates, can’t write or speak good English despite the training they have been receiving right from elementary to higher institution.

“How could one communicate properly in English language when he/she lacks the requisite foundation? Therefore, adopting the mother tongue as a way of instructing pupils in the nation’s primary schools is a major setback to education. The policy is indeed retrogressive, considering how students and graduates are battling with poor English communication,” Adeojo stated.

Teachers divided

A teacher, Esther Eliogu, said for a child’s intellectual enhancement, teaching in the local language is preferable and it will yield results. Eliogu said if they are taught in local languages, the level of assimilation would be high and we would be able to preserve the nation’s heritage.

She insisted that learning through mother tongue was the right of the child as it makes children strong in mental and social bonding.

“Learning does not begin in school. Learning starts at home in the mother language. Although the start of school is a continuation of this learning process, it also presents significant changes in the mode of education,” she said.

Another teacher, James Eboh, said: “Many education systems favour those using national or ‘global’ languages instead of mother tongue in teaching. Developing the use of mother tongue to deliver lectures poses a lot of challenges that should be addressed first before applying it.

“Sometimes in multilingual countries with many local languages, teachers do not speak the local language which the pupils learn at home. They speak the dominant language. In other cases, teachers themselves may not be fully proficient in the language of instruction. For example, how many Igbo teachers in Lagos speak Yoruba fluently?” he asked.

5 months ago

31

5 months ago

31

English (US) ·

English (US) ·