BBC

BBC

Warning: This story contains descriptions of sexual abuse.

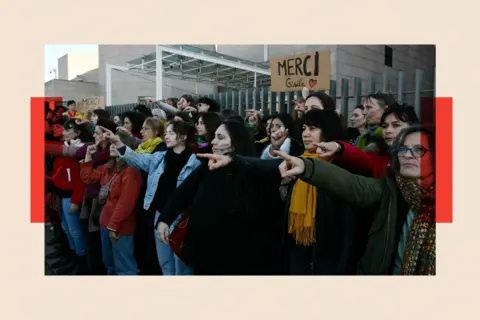

Each morning, the queues began forming before dawn. Groups of women – always women – stood in the autumn chill on a pavement beside a busy ring road, outside Avignon's glass and concrete courthouse.

They came, day after day. Some brought flowers. All wanted to be in place to applaud Gisèle Pelicot as she walked, purposefully, up the steps and through the glass doors. Some dared to approach her.

A few shouted: "We're with you, Gisèle," and "Be brave."

Most then stayed on, hoping to secure seats in the courthouse's public overflow room from where they could watch proceedings on a television screen. They were there to bear witness to the courage of a grandmother, as she sat quietly in court, surrounded by dozens of her rapists.

"I see myself in her," said Isabelle Munier, 54. "One of the men on trial was once a friend of mine. It's disgusting."

"She's become a figurehead for feminism," said Sadjia Djimli, 20.

But they came for other reasons too.

Above all, it seemed, they were looking for answers. As France digests the implications of its largest rape trial, which is due to end this week, it's clear that many French women – and not just those at the courthouse in Avignon – are pondering two fundamental questions.

Getty Images

Getty Images

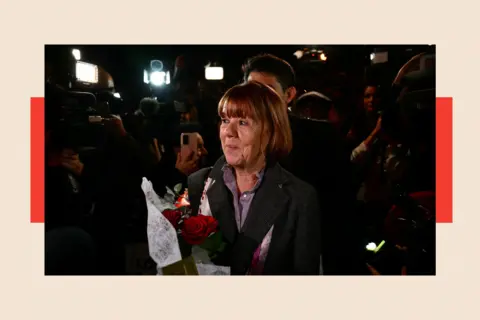

Ms Pelicot is met by women outside the Avignon courthouse after the prosecution concluded its case

The first question is visceral. What might it say about French men – some would say all men – that 50 of them, in one small, rural neighbourhood, were apparently willing to accept a casual invitation to have sex with an unknown woman as she lay, unconscious, in a stranger's bedroom?

The second question emerges from the first: how far will this trial go in helping to tackle an epidemic of sexual violence and of drug-facilitated rape, and in challenging deeply held prejudices and ignorance about shame and consent?

Put simply, will Gisèle Pelicot's courageous stand and her determination – as she has put it, to make "shame swap sides" from the victim to the rapist – change anything?

Behind the masks of the accused

A long trial creates its own microclimate and, over the past weeks, a strange sort of normality developed inside Avignon's Palais de Justice. Amid the TV cameras and the huddles of lawyers, the sight of dozens of alleged rapists – faces not always hidden behind masks – no longer provoked the shock it had at the start.

The accused strolled around, chatting, joking, grabbing coffee from the machine or returning from a café across the road, and, in the process, somehow emphasised the core argument of their various defence strategies: that these were just regular guys, a cross-section of French society, who were looking for a "swinging" adventure online and got caught up in something unexpected.

"[That argument is] the most shocking thing about this case. It's harrowing to think about it," says Elsa Labouret, who works for a French activist group, Dare to be Feminist.

"I think most people in long-term relationships with men think of their partner as someone trustworthy. But now there's this sense of identification [with Gisèle Pelicot] for a lot of women. Like, 'okay, so that can happen to me'.

"These are not criminal masterminds," she continues. "They just went on the internet... So, it is possible similar things are happening everywhere." It's a view widely held, but also widely contested in France.

France's Institute of Public Policies released figures in 2024 showing that on average, 86% of complaints of sexual abuse and 94% of rapes were either not prosecuted or never came to a trial, in the period between 2012 and 2021.

Ms Labouret argues that sexual violence happens when certain men know that they "can get away with it. And I think that's a big reason why it's so rampant in France."

'Neither monsters nor ordinary men'

Throughout the four-month trial, at the end of each courtroom break, the accused would gather by the metal detector before muscling past the mostly female press corps, also waiting to enter the chamber. Inside, one by one, the men took their turn to share their accounts.

A court-appointed psychiatrist Laurent Layet testified that the accused were neither "monsters" nor "ordinary men". Some wept. A few confessed. But most offered an array of excuses, with many saying they were simply "libertines" – as the French put it – indulging a couple's fantasies, and that they had no way of knowing Ms Pelicot had not consented. Others claimed Dominique Pelicot had intimidated them.

There are very few clear patterns or shared characteristics among the 51 men on trial. They represent a wide spectrum in society: three-quarters have children. Half are married or in a relationship. Just over a quarter of them said they had been abused or raped as children.

There is no discernible grouping by age or job or social class. The two traits they all share are that they're male, and that they made contact on an illicit online chat forum called Coco, known for catering to swingers, as well as attracting paedophiles and drug dealers. According to French prosecutors, the site, which was shut down earlier this year, has been cited in more than 23,000 reports of criminal activity.

The BBC has found that 23 of those on trial – or 45% – had previous criminal convictions. Although the authorities do not collect precise data, according to some estimates that is approximately four times the national average in France.

"There's no typical profile of men who commit sexual violence," concluded Labouret.

One person who has followed the case more closely than most is Juliette Campion, a French journalist who has been in court throughout the trial to report for the public broadcaster France Info. "I think this case could have happened in other countries, of course. But I think it says a lot about how men see women in France… About the notion of consent," she says.

"A lot of men don't know what consent actually is, so [the case] says a lot about our country, sadly."

'A matter of Mr Everyman'

The Pelicot case is certainly helping to shape the contours of attitudes to rape across France.

On 21 September, a group of prominent French men, including actors, singers, musicians and journalists, wrote a public letter that was published in Liberation newspaper, arguing that the Pelicot case proved that male violence "is not a matter of monsters".

"It is a matter of men, of Mr Everyman," the letter said. "All men, without exception, benefit from a system that dominates women."

It also sketched out a "road map" for men seeking to challenge the patriarchy, with advice such as "let's stop thinking there is a masculine nature that justifies our behaviour".

Some experts believe the huge public interest in the Pelicot case could already be producing benefits.

"This whole case is so useful for everyone, for all generations, for young boys, for young girls, for adults," says Karen Noblinski, a Paris-based lawyer specialising in sexual assault cases.

"It has raised awareness in young people. Rape doesn't always happen in a bar, in a club. It can happen in our home."

The NotAllMen hashtag

But there is clearly much more work to be done. I went to meet Louis Bonnet, who is the mayor of the Pelicots' home village, Mazan, early on in the trial. Although he was unequivocal in condemning the alleged rapes, he stated clearly and twice that he felt Gisèle Pelicot's experience had been overblown, and argued that as she'd been unconscious, she had suffered less than other rape victims.

"Yes, I am minimising it, because I think it could have been much worse," he said at the time.

"When there are kids involved, or women killed, then that is very serious because you can't go back. In this case, the family will have to rebuild itself. It will be hard, but no one died. So, they can still do it."

Bonnet's comments provoked outrage across France. The Mayor later issued a statement, expressing his "sincere apologies".

Getty Images

Getty Images

Women gather in support of Gisèle Pelicot outside the Avignon courthouse

Online, many of the debates around the case have focused on the controversial suggestion that "all men" are capable of rape. There's no evidence to support such a claim. Some men have pushed back against the argument, using the hashtag #NotAllMen.

"We do not ask other women to bear the 'shame' of women who behave badly, why should the mere fact of being a man qualify us to bear the shame?" asked one man on social media.

But the pushback was swift. Women reacted to the #NotAllMen hashtag with anger and, sometimes, with details of their own abuse.

"The hashtag has been created by men and used by men. It's a way to silence the suffering of women," wrote journalist Manon Mariani. Later, a male musician and influencer, Waxx, added his own criticism, telling the hashtag users to "shut up once and for all. It's not about you, it's about us. Men kill. Men attack. Period."

Elsa Labouret believes French attitudes still need challenging. "I think a lot of people still think that sexual violence is sexy or romantic or something that is part of the way that we do things here [in France]," she argues.

"And it's so important that we question that and that we don't accept this kind of argument at all."

Chemical submission and proof

In her small office just behind the French parliament building on the River Seine, Sandrine Josso, an MP, has a four-letter swearword on a poster beside her desk. It captures the spirit of defiance and determination that is driving her campaign against what's known in France as "chemical submission", or drugging in order to rape.

A year ago, in November 2023, she was at a party in the Paris apartment of a senator named Joel Guerriau. She claims that he put a drug in her champagne with the intention of raping her. Geuerriau has denied attempting to drug her, blaming a "handling error" and telling investigators that the glass had been contaminated a day earlier.

In a statement, his lawyer has said: "We are miles away from the obscene interpretation that one might infer from reading initial reports in the press." A trial is anticipated next year.

Josso is now campaigning, as she puts it, to "make victims' journeys easier" when it comes to the French legal system.

"Today, it's a disaster. Because very few victims who file complaints are able to have a trial, because of the lack of evidence. [There's not] enough medical, psychological or legal support. We find shortcomings everywhere when it concerns sexual violence."

Josso has now joined forces with Gisèle Pelicot's daughter, Caroline, to put together a drug-testing kit that could be made available in pharmacies throughout France. It now has government backing for a trial rollout, helped by the publicity generated by the Pelicot case.

"I'm optimistic. The medical world and the French people want shame to change sides [from the victim to the accused]," says Josso, quoting the phrase made famous by Gisèle Pelicot.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Ms Pelicot's daughter Caroline

But Dr Leila Chaouachi, a chemist and expert at the Paris Addiction Monitoring Centre, says that the trial in Avignon is just one step in a long struggle to make people more aware of drugs and rape.

"It needs to become a real major public health issue that everyone takes seriously, and which forces the authorities to urgently address these issues to improve care for victims.

"It's important for all of us to think about the issue, to consider it a health issue, not just a justice issue. It concerns all of us."

At present the word "consent" is not included in the definition of rape in French laws, so some have argued that it should be changed to make it more explicit. But Ms Noblinski believes the focus should be elsewhere.

"[It] should be on the police, on the investigations, on funding them properly, not on tinkering with the law," she says. "They don't have sufficient resources. They have too many cases, and that's the real issue. When you have too many things to handle, it's very hard to find evidence."

Getty Images

Getty Images

Ms Pelicot carries flowers as she leaves the Avignon courthouse

On her daily commute to the courthouse, during the first weeks of the trial, Gisèle Pelicot walked with her shoulders hunched and her posture defensive. She seemed flustered by the sheer level of interest the case generated. By the closing arguments, however, her demeanour was entirely different and she sat perfectly poised.

That has coincided with a greater change: as the trial progressed, the prosecution, those watching – and Mrs Pelicot herself – came to understand the extraordinary impact of her decision to opt not just for an open trial, but for every detail to be shown in court.

"She's showing us that… if you're a victim… do your best not to carry shame. Keep your head high," says Elsa Labouret.

"As a woman, you start by being doubted. You start off as a liar and you have to prove that it's true. I don't doubt that every woman has been through something. Something, you know. In that way she represents all the women in the world.

"[Gisèle Pelicot] decided to make this bigger than herself. To make this about the way that we, as a society, treat sexual violence."

Emerging from yet another day in the courtroom, the French journalist Juliette Campion stopped to reflect on what impact the case might have. "It was difficult to see all those videos... As a woman, it's complicated, and I feel tired," she says.

"But at least we did our job, and we talked about it. It's a very small step. It won't be a big thing. The only thing I can hope for now is that it will be a game changer for some men. And some women too, maybe."

BBC InDepth is the new home on the website and app for the best analysis and expertise from our top journalists. Under a distinctive new brand, we’ll bring you fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions, and deep reporting on the biggest issues to help you make sense of a complex world. And we’ll be showcasing thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. We’re starting small but thinking big, and we want to know what you think - you can send us your feedback by clicking on the button below.

1 week ago

3

1 week ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·