BBC

BBC

Donald Trump has been unclear about whether he will impose tariffs on the UK but economists warn there are still ways Britain could be negatively affected by the president's wider trade policies even if it avoids being hit directly.

The impact could be felt through slower growth in some of the UK's important trading partners. Industrial exports could be diverted from the US and flood the UK market and there could be impacts on our financial markets, including a possible increase to borrowing costs.

Asked about future tariffs, Trump told the BBC on Sunday night: "The UK is way out of line but I'm sure that one… I think that one can be worked out."

The president did not specify in which way he regarded the UK as being "out of line".

One of the justifications Trump has given for imposing tariffs on countries is they have a trade surplus with the US - in other words they sell more to the US than they import from America.

He has claimed these trade surpluses amount to "massive subsidies that we're giving to Canada and to Mexico".

The tariffs on Mexico were paused for a month by Trump on Monday but the president has complained about unbalanced trade with the EU, saying on Sunday: "they don't take our cars, they don't take our farm products, they take almost nothing and we take everything from them. Millions of cars, tremendous amounts of food and farm products".

So one way the UK might be seen to be out of line in the mind of Trump - and at risk of tariffs - is if Britain was also running a trade surplus with America.

Does the UK have a trade surplus with the US?

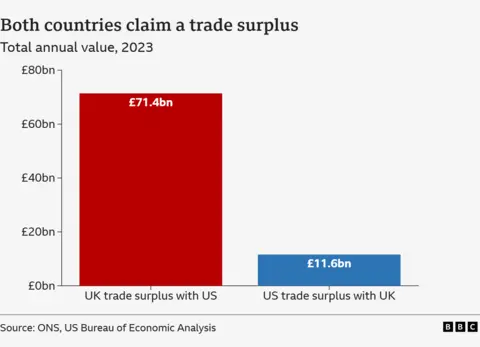

The UK's Office for National Statistics estimates the UK had a surplus of around £71bn in trade with the US in 2023, the most recent full year for which we have data.

But the American statistics office, the Bureau of Economic Analysis, estimates the US had a surplus on its trade with the UK in that year of $14.5bn, around £12bn.

How can both be true?

The two stats agencies have looked at this discrepancy and agree it is due to different ways of measuring trade.

One factor is the UK agencies, unlike their US counterparts, do not count trade flows through British crown dependencies such as the Isle of Man, some of which are significant financial services hubs and markedly affect the overall figures.

Another key, related, element seems to be differences in the measurement of services trade - things such as banking and finance - as opposed to physical goods.

But the bottom line is there is still a degree of uncertainty about what precisely is driving the overall difference in the statistics and both agencies are trying to work it out.

In the meantime, the UK government will doubtless be hoping President Trump prefers to use the US data, which shows America is selling more to the UK than it is buying - and will focus on the goods rather than services trade.

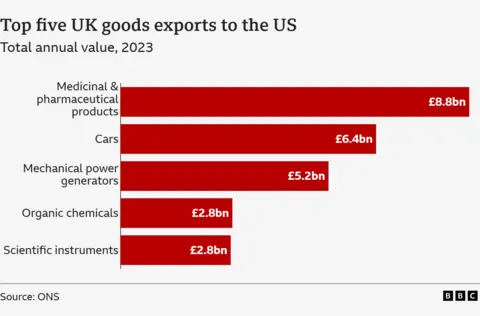

If the President were to impose a blanket tariff on UK exports to the US it would affect around £60bn of goods sent in 2023, according to the UK's figures.

Pharmaceutical products accounted for £8.8bn of the UK's goods exports to the US in that year, cars £6.4bn and power generation machinery £6.4bn.

While the immediate impact of the tariffs would be to make the price of these imported goods for US firms and consumers higher, over time they could reduce American demand for them, which could have a negative impact on the UK firms exporting them.

How else could the UK be affected?

There are other ways in which Britain could be negatively affected by US tariffs on other countries.

Slower growth in the global economy and, in particular, the EU - with which the UK still does around half of its trade - would impede the UK's growth prospects.

If our trading partners were to fall into recession due to tariffs, analysts say they would cut interest rates and their currencies would drop in value making British exports to them more expensive.

"The US imposing tariffs on our other trading partners will still have a negative effect on the UK economy through its effect on supply chains and the exchange rate," said Ahmet Kaya, of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR).

Niesr has estimated that the 25% tariffs the US has threatened to impose on Mexico and Canada could reduce UK GDP growth by 0.1 percentage points in 2025.

Some economists warn exports - such as Chinese-made steel - that might get diverted from the US markets due to the new tariffs, could be sold at below the cost of production, or "dumped" in UK markets, which might have a negative impact on the sales of UK steel producers.

Some analysts say higher US interest rates as a result of the tariffs could also spill over to UK borrowing markets.

One of the reasons UK government borrowing costs, or Gilt yields, temporarily spiked upwards in January, was because American government bond yields had also risen.

"The main threat to the UK economy from Trump's tariffs may well be the spillover from higher US interest rates, rather than tariffs themselves," says the economist Julian Jessop.

"US and UK government bond yields are now moving in lockstep again. If the Fed [US central bank] is more reluctant to cut US rates, as seems likely, borrowing costs will be higher for longer in the UK as well."

Higher borrowing costs could slow the UK economy and also put pressure on the UK government to cut public spending or raise taxes in order to keep within its chosen borrowing rules.

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1

English (US) ·

English (US) ·