It seems that in Nigeria, patriotism is often invoked to question the decisions of Nigerian scholars who choose to work abroad rather than return to their homeland. This critique, however, may be misdirected. The core issue is not the physical presence of highly skilled Nigerians but rather the structural inefficiencies that limit their potential impact within the country. Rather than scrutinising the patriotism of people based on their location, the discussion should center on how Nigeria’s systems stymie the expertise they have painstakingly developed abroad, rendering their return an exercise in unrealised potential. This “brain drain” narrative, which blames people for not returning to Nigeria after advanced studies abroad, ignores the real reasons they hesitate to come back. Many Nigerians would eagerly return if meaningful opportunities aligned with their skills existed. But in a system plagued by power outages, inadequate research facilities and inconsistent funding, it is practically impossible for them to operate at their highest capacity. For many Nigerian scholars, staying abroad does not equate to a lack of patriotism but instead a recognition of where they can most effectively contribute to their country and the world at large.

A common belief among many Nigerians is that past generations who studied abroad and returned were somehow inherently more patriotic or virtuous than today’s scholars. This belief ignores both the historical and contemporary realities of human nature. As modern thinkers like Robert Greene, along with classic philosophers such as Machiavelli and Freud, have argued, human nature is complex, with people always exhibiting a mix of self-interest and community spirit. This has not changed over the centuries. Returning to Nigeria after studying abroad in previous generations was not solely driven by altruism or sacrifice, but, often, the opportunities and social context back then were more conducive to returning. Today’s circumstances are vastly different, and the narrative that “people were better back then” oversimplifies a complex reality. Scholars who decide to stay abroad today are not driven by a lack of morality or patriotism but rather by a rational assessment of the conditions they would face upon their return and the likelihood of realising their professional goals in Nigeria. The belief that Nigerian scholars should simply “pay their bonds and move on” also fails to address the deeper, systemic issues at play. While fulfilling contractual obligations is important, reducing the issue to moral compliance oversimplifies a complex situation. When a scholar is unable to find the necessary resources, infrastructure, or support to conduct meaningful work in Nigeria, expecting them to return and contribute meaningfully to the country becomes unrealistic. This perspective overlooks the reality that patriotism and the desire to contribute exist independently of one’s physical location.

A Nigerian with a PhD from a top UK institution returning to a public university in Nigeria often faces significant barriers. Nigeria’s public universities, constrained by limited infrastructure and chronic power issues, frequently lack the resources needed to leverage advanced training. For instance, complex experiments that require constant power and stable conditions may be virtually unfeasible due to persistent power outages. I recall one experiment conducted during my PhD that required continuous exposure of samples to precise pressure-temperature and salinity conditions for nine months at the British Geological Survey. A single power failure would have invalidated months of work. Returning to a system that cannot sustain such projects is a missed opportunity not only for the scholar but for Nigeria itself.

The argument that certain Nigerian professionals, particularly in medical fields, publish research in reputable journals and thus demonstrate the country’s research capability needs closer scrutiny. It may be true that some Nigerian researchers contribute to global scholarship, but it is challenging to identify transformative solutions to critical health challenges, like malaria, sickle cell anemia or gynecological conditions, that originated from Nigeria’s research environment and have had a significant global impact. This limitation highlights a systemic issue, which is the inability of the Nigerian academic and research system to foster groundbreaking, globally influential innovations. Without verifiable evidence of Nigerian-originated medical breakthroughs addressing global or local health crises, it is difficult to argue that the research environment in Nigeria is sufficiently robust to support world-class scientific progress. These further stresses the point that the structural deficiencies, such as inadequate funding, limited infrastructure and unreliable systems, pose significant barriers to producing high-impact research. For Nigerian scholars, the challenge is not just patriotism but the reality of an environment that limits their ability to make meaningful contributions to both local and global problems.

This systemic weakness undermines the claim that Nigeria provides an enabling platform for globally acknowledged research in most fields, including medicine. If some Nigerians argue that the country’s public universities are performing at a level where graduates who study in Western countries can return and make meaningful contributions, this claim can be easily challenged. One might ask why Nigerian public universities are predominantly staffed by Nigerians, at least 99 percent of the faculty and staff are local in most public universities. If it were true that people with advanced degrees, particularly in STEM fields, could seamlessly reintegrate and thrive in Nigerian universities, we would expect to see a significant presence of academic staff from other nationalities. Globally, universities are considered universal institutions, attracting talent from diverse backgrounds and nations. The absence of such diversity in Nigerian public universities suggests otherwise. It indicates that their dominance by Nigerians may stem less from the applicability of advanced skills acquired abroad and more from factors like national ties and personal circumstances. This observation undermines the argument that skills gained through foreign education can readily be applied within the Nigerian public university system.

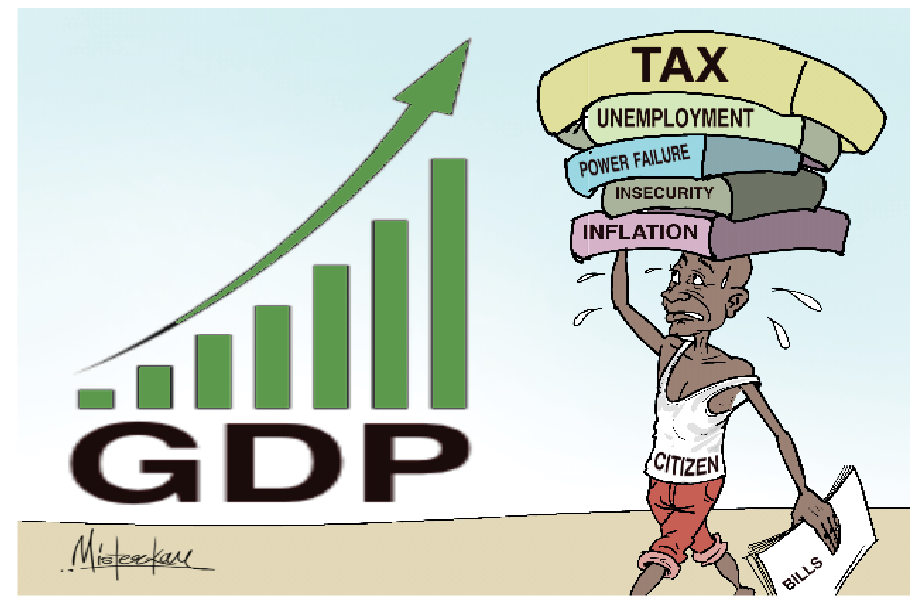

Also, even the most advanced training abroad can become obsolete or underutilized in Nigeria’s academic environment. In virtually all technical fields, researchers are often unable to build on their expertise or contribute innovative solutions due to the lack of infrastructure and specialized resources. Returning to Nigeria then becomes more about surviving the system’s limitations than creating groundbreaking impact. Scholars trained to address complex issues like energy, climate and technology find themselves restricted to tasks that barely utilize their capabilities, leading to professional stagnation and unfulfilled potential. Patriotism should not be measured by geographic location but by the intent and impact of one’s work. Many Nigerian professionals, myself included, work from various parts of the world and contribute to the African continent’s development. My work, for instance, focuses on creating positive impact for Africa, despite being globally oriented. In some cases, those based abroad can make a more meaningful impact than those who remain physically present on the continent. Through international research collaborations, funding streams or policy advocacy, Nigerians abroad can drive change in ways that transcend borders. Nigerian institutions need to recognize that, in a globally connected world, physical presence within Nigeria is not a requisite for impactful contribution. Another argument often made is that scholars on government-sponsored scholarships should fulfill return bonds regardless of Nigeria’s internal conditions. This view overlooks the purpose of these contracts, which is to create opportunities for scholars to apply their skills for national benefit. If the environment does not support or value their expertise, enforcing bond obligations becomes counterproductive. Scholars returning to conditions that fundamentally hinder their work contribute little to national development. The concept of force majeure is also relevant here. Typically invoked in contractual law to relieve parties from obligations due to extraordinary circumstances beyond their control, force majeure reflects the lived realities in Nigeria. Power failures, inadequate infrastructure and security issues in certain regions fundamentally alter the context in which these bonds were initially signed. Recent reports highlight how cities especially in northern Nigeria have been without electricity for days, leaving hospitals, businesses and educational institutions in crisis. For scholars expected to return to such conditions, fulfilling their bond is more an exercise in personal sacrifice than a contribution to national progress.

Under these circumstances, enforcing a bond can seem unjust. The value of a bond is lost if it fails to fulfill its purpose of fostering national development. Requiring, for example, a nuclear engineering expert to return to a university without facilities for nuclear research undermines both the person’s potential and the nation’s goals. The question becomes not whether bonds should be enforced but whether the conditions allow these scholars to contribute meaningfully upon their return. For many Nigerian PhDs, securing high-paying jobs abroad makes fulfilling their bonds not just feasible but relatively trivial in financial terms. While the debate often frames bond repayment as a significant financial burden, it is worth noting that well-paying employers in Nigeria rarely impose these bonds. Lower-paying institutions, however, tend to bond employees, and the sum typically involved is a fraction of the salary many scholars earn abroad. For scholars in STEM fields, where they can quickly earn enough to offset years of Nigerian university salaries, fulfilling these bonds is not a difficult task.

Nigerians need credible journalism. Help us report it.

Support journalism driven by facts, created by Nigerians for Nigerians. Our thorough, researched reporting relies on the support of readers like you.

Help us maintain free and accessible news for all with a small donation.

Every contribution guarantees that we can keep delivering important stories —no paywalls, just quality journalism.

Addressing this complex problem would require Nigerian institutions to create more attractive conditions for skilled professionals. Simply enforcing bond repayment does little to tackle the root causes preventing scholars from returning. If we want to stop this cycle of talent loss, the focus should be on creating a supportive environment that aligns with the expertise and aspirations of returning scholars. These reforms might include improved infrastructure, competitive salaries and research funding that empowers scholars to continue their work at an international level from within Nigeria. Framing the issue solely as a moral obligation for PhDs to return home and fulfill their bonds by teaching undergraduates or managing operational issues in Nigerian public universities is neither practical nor respectful of their training. No one pursues a PhD solely to manage issues like water, electricity or security problems that do not require advanced degrees to solve. Enforcing return bonds without addressing these fundamental barriers will only prolong this discussion for decades. The issue is not about morality but about building a system that can support and make use of advanced expertise. Scholars are not defaulters in a moral sense but people making rational choices based on the conditions they face.

The suggestion that past generations who returned were more self-sacrificing overlooks the structural and economic changes over time. Scholars today face a global job market where they are not only able to work abroad but also to be compensated according to their skills. This was not necessarily the case in previous generations, where both the global job market and Nigeria’s own systems were different. Rather than viewing these scholars as morally deficient for choosing to stay abroad, we should recognize the limitations of Nigeria’s institutions in providing the environment they need to thrive. If we are serious about tackling the root causes of bond breaches, we need a systemic approach that goes beyond enforcing repayment. Many scholars who choose not to return do so because they have found significantly better opportunities abroad, where just a few months’ salary can offset the entirety of their bond obligations. Expecting them to return and serve in environments that do not allow them to use their skills fully is a disservice not only to the scholars themselves but to the nation’s potential for development. Rather than focusing on morality, the solution lies in building a system that provides these scholars with the support and resources they need to thrive at home.

Enforcing bond repayments without addressing the structural issues will only perpetuate the cycle of talent loss. Paying back a few million naira in university salaries, whether in installments or all at once, does little to resolve the larger problem or prevent future breaches. A truly patriotic approach would involve creating sustainable systems that allow skilled Nigerians to return and contribute effectively to national growth. Until this happens, we will continue to lose some of our brightest minds to systems that offer the respect, resources, and compensation that their expertise deserves. That said, addressing Nigeria’s brain drain requires moving past superficial solutions and moral arguments. Scholars are not leaving because they lack patriotism or morality. They are leaving because the systems at home are not yet ready to support their work. The focus should be on building environments that respect and empower these scholars by offering them the opportunity to return and make a meaningful impact. Only then can Nigeria truly reverse the brain drain and create a future where talented professionals can thrive at home.

Mohammed Dahiru Aminu (mohd.aminu@gmail.com) wrote from Abuja, Nigeria.

Support PREMIUM TIMES' journalism of integrity and credibility

At Premium Times, we firmly believe in the importance of high-quality journalism. Recognizing that not everyone can afford costly news subscriptions, we are dedicated to delivering meticulously researched, fact-checked news that remains freely accessible to all.

Whether you turn to Premium Times for daily updates, in-depth investigations into pressing national issues, or entertaining trending stories, we value your readership.

It’s essential to acknowledge that news production incurs expenses, and we take pride in never placing our stories behind a prohibitive paywall.

Would you consider supporting us with a modest contribution on a monthly basis to help maintain our commitment to free, accessible news?

TEXT AD: Call Willie - +2348098788999

English (US) ·

English (US) ·