A blood bag is hung on a wall, its contents trickling through an intravenous line into Sadiya Ibrahim’s right arm as she lay almost lifeless on a raffia mat. The pregnant woman occasionally raises her frail hand to swat flies around her face. All the time, she fails.

For three days in March, excruciating pains around her stomach and waist rendered her helpless at her home at Garin Liman, a village in Batsari Local Government Area (LGA) of Katsina State. However, no commercial vehicles or motorcycles plied the road to the primary healthcare centre (PHC) in Batsari, more than 10 kilometres away.

Mrs Dudua (right) and other relatives took turns pushing an ailing Sadiya Ibrahim (left) in a cart in search of healthcare

Mrs Dudua (right) and other relatives took turns pushing an ailing Sadiya Ibrahim (left) in a cart in search of healthcareEventually, her sister, Dudua, and other concerned relatives settled for a cart. They took turns pushing the two-wheeled ‘vehicle’ for several kilometres before arriving at Dantsuntsu, another village in Batsari. They laid her on a mat in an empty room beside a pharmacy where residents from neighbouring villages visit for urgent and minor health-related problems. A health worker recommends and sells drugs to the villagers at the pharmacy. In rare cases, he treats people like Mrs Ibrahim, a resident who identified as Kasim told PREMIUM TIMES.

“We couldn’t find a motorcycle to convey her,” Mrs Dudua said, watching her sister’s breath as if to be sure she was still alive. “Those with motorcycles are scared of riding it here.”

Medical deserts

The only health centre at Garin Liman was shut years ago after health workers deserted it due to fear of attacks by terrorists, locally known as bandits. The bandits have attacked health facilities and health workers across Katsina and Zamfara states, jeopardising access of residents to essential healthcare services.

The trouble that started as a cattle rustling challenge a little over a decade ago has metamorphosed into full-blown terrorism that has left horrid scars and gory tales across north-west Nigeria. Scattered across the region are terrorist gangs whose persistent violent attacks have halted everyday life in rural communities. They plundered villages and carted away animals and farm produce. In what has now become a multi-million naira industry, they kidnap for ransom, impose levies on communities and use residents for forced labour.

In Nigeria’s Northwest, access to healthcare is in shambles

In Nigeria’s Northwest, access to healthcare is in shamblesTerrorists’ activities have affected primary healthcare delivery in the region, exacerbating maternal and neonatal mortality, child health issues and malnutrition.

Nigerians need credible journalism. Help us report it.

PREMIUM TIMES delivers fact-based journalism for Nigerians, by Nigerians — and our community of supporters, the readers who donate, make our work possible. Help us bring you and millions of others in-depth, meticulously researched news and information.

It’s essential to acknowledge that news production incurs expenses, and we take pride in never placing our stories behind a prohibitive paywall.

Will you support our newsroom with a modest donation to help maintain our commitment to free, accessible news?

Due to terror activities, at least 69 health centres have been shut across Batsari, Jibia, Safana, Faskari and Sabuwa LGAs of Katsina State. In Batsari LGA alone, 19 health centres are currently closed, according to information obtained from a civil servant at the Katsina State Ministry of Health. Until recently, there was only one medical doctor in the community of over 300,000 people.

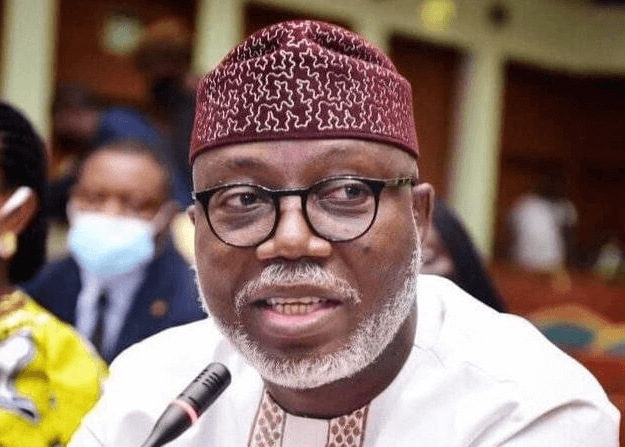

“Now, we have two,” said Adamu Saminu, chairperson of the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA), Katsina State Chapter.

“There was a time we had only one doctor because nobody would want to go and stay in Batsari because of the fear for their lives.”

Like Katsina, like Zamfara

The situation is similar in neighbouring Zamfara State, where many workers have abandoned health centres, creating healthcare deserts in Anka, Shinkafi, Zurmi and Maru LGAs.

Abandoned health centre due to terrorist activities

Abandoned health centre due to terrorist activitiesIn 2022, Zamfara State was the most difficult state in Nigeria to access primary healthcare, according to a report jointly produced by ONE Campaign, National Advocates for Health, Nigeria Health Watch, and the Public and Private Development Centre (PPDC).

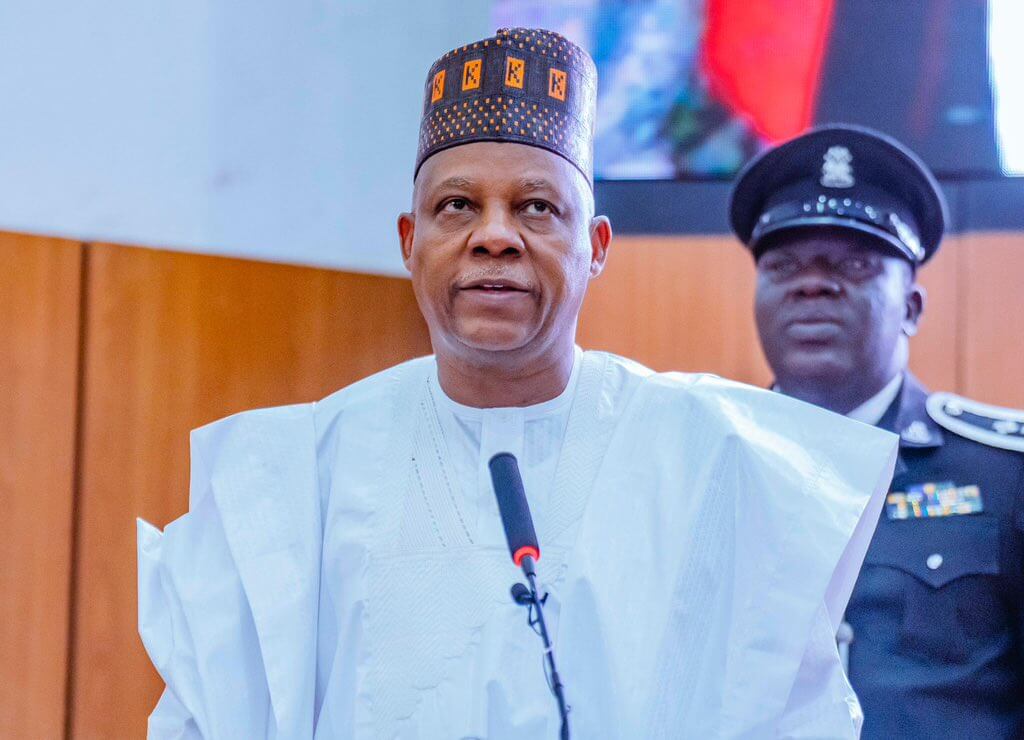

In 2023, Husaini Anka, the Executive Secretary of the state’s Primary Healthcare Board, disclosed that due to insecurity, only about 200 of the state’s 700 PHCs were functional.

Worryingly, the situation isn’t slowing down as attacks on communities continue to increase.

According to a study published in the Global Biosecurity Journal, this deeply troubling situation is multifaceted and has far-reaching implications for healthcare providers and recipients.

Residents of many troubled rural communities in the North-west now travel many kilometres to access the most basic healthcare services.

“It is either the infant dies because of inadequate healthcare or the mother dies of stress and suffering,” Mrs Dudua said of the situation in her community.

Worsening maternal mortality

Safiya Shuaibu has little energy left in her. She utters each word laboriously. The 30-year-old had delivered her eighth child only 12 days before this interview. She has been in and out of the health centre, where she is receiving a blood transfusion for the second day.

Mrs Shuaibu lives in Kofa, a village about seven kilometres from the Nahuta Health Centre in Katsina State, where PREMIUM TIMES met her. It is the only one accessible to residents of Kofa, Tashan Modibbo, Madogara, Zamfarawa, Kasai and Sabon Garin Dumburawa since the other health centres in the communities were shut. Though the centre was marked for an upgrade to a Maternal and Child Health (MCH) centre, that plan stalled due to the insecurity in the area, said a Community Health Extension Worker (CHEW) who didn’t want to be named.

Mrs Shuaibu was-forced-to-give-birth-to-her-daughter-at-home-as-the-health-centre-in-her-community-had-been-shut-

Mrs Shuaibu was-forced-to-give-birth-to-her-daughter-at-home-as-the-health-centre-in-her-community-had-been-shut-The new mother walked long distances to and from the health centre daily to continue the blood transfusion as the hospital does not operate beyond dusk. “You can’t get a motorcycle to bring you here,” a worn-out Mrs Shuaibu said.

On this Tuesday in March, she took multiple breaks to rest on her way to the health centre. “Even yesterday, after they were done transfusing blood, I walked home,” she told PREMIUM TIMES.

When she went into labour, there was no health centre close to her, forcing her to give birth to her daughter at home in Kofa.

Her fate is hardly unique.

In Zamfara and Katsina states, less than 20 per cent of deliveries benefit from skilled attendance at birth, according to the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) progress report on improving maternal and newborn health and survival and reducing stillbirth. Studies have also linked the utilisation of unskilled attendance at birth to maternal and neonatal deaths.

Also, by accounting for 12 of every 100 maternal and neonatal deaths and stillbirths globally, Nigeria has the second-highest Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR) in the world — second only to India, according to WHO.

Less than 20 per cent of deliveries in Katsina, Zamfara Sokoto and Bauchi states benefit from skilled attendance at birth. Credit_ WHO Report

Less than 20 per cent of deliveries in Katsina, Zamfara Sokoto and Bauchi states benefit from skilled attendance at birth. Credit_ WHO ReportNigeria is expected to reduce the maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births in six years to meet the global target for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 3.1. But the country still records over 1,000 deaths per 100,000 live births, raising concerns regarding the country’s ability to meet the target.

Though there is no comprehensive data for troubled communities in the Northwest, the situation is worsening, said Mr Saminu, who leads the doctors’ union in Katsina State. He noted that the North-west has the highest maternal mortality in the country.

“Putting this in perspective on what is happening currently, you know that the situation is worsening by the day,” he said.

MMR Data, National Average and Katsina and Zamfara Data. The picture from the WHO document shows the low access to SAB.

MMR Data, National Average and Katsina and Zamfara Data. The picture from the WHO document shows the low access to SAB.Failing immunisation eroding herd immunity

Almost two weeks after she gave birth, Mrs Shuaibu said her daughter had not received any immunisation. She was told to come back at a later date.

According to the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency’s (NPHCDA) routine immunisation schedule, infants are expected to take three vaccines at birth. The vaccines include the Bacillus Calmette-guérin (BCG), a vaccine to prevent tuberculosis and other mycobacterial infections; the oral polio vaccine (OPV); and the Hepatitis B vaccine.

However, only a few women from these communities visit the available health centres for their children’s immunisation, Hadiza Musa, a community health worker at the family healthcare support at PHC Batsari, said.

She said those who do walk long distances because commercial motorcycles or vehicles are absent in their communities.

“A lot of them (women) don’t come for ante-natal care too,” said Ms Musa, who also used to work at a now-shut health centre in Dangeza, another troubled community.

Meanwhile, routine immunisation has increasingly become difficult in rural communities as terrorists have stolen and destroyed some of the freezers and solar panels for electricity used for the safekeeping of vaccines, one health official who works in Batsari LGA told PREMIUM TIMES.

The official, who did not want to be named as they have no authority to provide this information, said some children have zero doses of essential immunisation, leading to the resurgence of preventable diseases in these communities.

The source noted, for instance, that three cases of a rare form of the wild poliovirus — the circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV)— were confirmed in the local government area in 2023, and one already confirmed in the first quarter of the year.

While cVDPVs are rare, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative said they have increased in recent years in communities with low immunisation rates, spreading from one unvaccinated child to another.

The first case was a kid from Manawa, a ward in Batsari LGA, who had zero doses of the polio vaccine and other routine immunisation. The official said the others are from Ruma, Darini and Kandawa wards.

“As a rule, we take samples of suspected persons alongside three other persons they have had contact with even when the contacts have not shown any symptoms,” he explained.

This year, at least eight samples of suspected acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) have been taken from Batsari LGA and sent for laboratory tests. Measles, yellow fever and diphtheria are also becoming commonplace.

The official noted that there were 63 cases of diphtheria from the LGA in 2023, adding that there are already six suspected cases this year.

“Now, what is being done is that the people from those localities are being trained and deployed to those areas for routine immunisation,” he said.

According to Mansur Oche, a professor and public health consultant at the Usmanu Danfodiyo University Teaching Hospital (UDUTH), this low immunisation coverage, leading to the loss of herd immunity, is why the outbreak of epidemics like measles and diphtheria readily claim a lot of casualties.

“If we want the immunity to improve, it means we must have close to 90 per cent of the children immunised so that once there is an outbreak, you already have coverage, they already have immunity,” he said.

“The cVDPV you are talking about is a result of low immunity in the community. The low immunity results from the fact that most of the children are not covered,” he added.

He explained that the cVDPV, a different variant of the popular poliovirus, is spreading because the region has many children with zero doses of the polio vaccines.

Mr Saminu fears that the situation will continue to compound unless there is security for health workers to administer routine immunisation to rural communities. He describes the situation as of serious concern that poses a greater risk to the entire country from a public health perspective.

He said: “It all boils down to the issue of insecurity because if you cannot guarantee my security, there is no way I will go to those areas and provide them with vaccines.”

“I know there are a lot of efforts by the National Primary Healthcare Development Agency and other development partners to see how they can come around and see how vaccines will be provided to such areas without putting the life of the healthcare workers at risk.”

For health workers, staying back has a cost

Abubakar Aliyu, 58, has several unanswered questions; Where is Yusuf Alalula? Why was he arrested? What happened to him and where is his corpse?

Two years have gone by but the questions remain unanswered. “All the information we have is just hearsay,” he said.

Abubakar Aliyu, 58, has several unanswered questions on the arrest and death of his brother, Yusuf Alalula.

Abubakar Aliyu, 58, has several unanswered questions on the arrest and death of his brother, Yusuf Alalula.Yusuf Alalula is a 60-year-old health worker and Mr Aliyu’s older brother. Mr Alalula, a community health extension worker, had worked for over 20 years at the health centre in Makakari, a village in Anka LGA, Zamfara State. Originally from Anka, he and his family lived in Makakari, where he worked.

Makakari is notorious for housing bandits and many residents have fled the village. Those who stayed have been forced into unpaid labour and to pay levies, including the purchase of a canoe for the terrorists.

“At some point, they started suspecting him of having a relationship with bandits,” Mr Aliyu said of his brother.

Yusuf Alalula has been missing and presumed dead since his arrest by ‘Yan Sakai more than two years ago.

Yusuf Alalula has been missing and presumed dead since his arrest by ‘Yan Sakai more than two years ago.“But as a health worker in Makakari, there was no way he could not have a relationship with them because they usually came for treatment of their wives, parents or children when they fell sick. Even if it requires stitching, they will come, and he must do it for them.”

One day, the Yan Sakai – a local vigilante group – seized Mr Alalula and took him away. It was the last they heard of him and his family now believes he is dead.

Ahmad, another of Mr Alalula’s brothers, said Mr Alalula was taken to a camp the vigilante shared with soldiers stationed in Anka against terror attacks.

“We waited and waited but about two to four months later, we learnt he died,” Mr Ahmad said.

Though their brother’s death remains a hearsay, it is all they hold on to since he went missing over two years ago. “We never saw his corpse but we heard he was tortured to death… if they had taken him to court, someone would have visited him at least for us to know he’s still alive,” Mr Aliyu said.

After the report of his death, Mr Alalula’s wife started and completed her ‘Iddah’, a four-month and 10-day waiting period for a Muslim widow. Then she remarried.

Fleeing terror

A few months before his retirement in 2023, Lawali Abdullahi, 55, stopped showing up at the health centre in Abare where he worked. He had escaped a couple of terror attacks. But he feared his luck was running out.

Mr Abdullahi, who started his career as a health extension worker over 30 years ago, worked at several health centres across Anka and Maru LGAs in Zamfara State. He witnessed how the once-peaceful communities gradually turned violent. He had worked in Bagega, Dankurmi, Ruwan Doruwa, and Danhayin Bawa, all now rife with bandits.

“When I worked at Ruwan Doruwa, everywhere was peaceful,” he recalled. “You could walk to Maru or anywhere without fear…the only thing you fear is a wild animal, and that’s if you come across any.”

Lawali Abdullahi made a decision to stop going to work when he feared his luck of evading bandits’ attack was running out.

Lawali Abdullahi made a decision to stop going to work when he feared his luck of evading bandits’ attack was running out.When the health centre at Tungan Addaka in Anka LGA was constructed some years ago, Mr Abdullahi was deployed to head the facility. When the security situation deteriorated, the authorities shut down the health centre. “The health centre was located along the route of the bandits,” he said.

Mr Abdullahi was then transferred to head the health centre in Abare, another volatile community in Anka LGA. When the attacks in Abare started getting more frequent, he made a decision. “I stopped going there,” he told PREMIUM TIMES

“It was already a few months to my retirement, so I stopped going there. When it was time to retire, I wrote and tendered my retirement notice. I retired on 1st November 2023.”

An aged problem

In northern Nigeria, complete immunisation coverage and adequate access to healthcare services have always been challenges. However, banditry has worsened the situation, making it more precarious, said Mr Oche, the medical consultant.

He said the abduction and attacks on health workers have also complicated the situation as health workers are resisting postings to such areas.

He added that villagers and health workers in the areas were at the mercy of “whatever is happening.”

“Now, the health workers are not there, services are not being rendered, medications are not going there… So it has made the health situation even more precarious now,” he said in a telephone conversation.

“So, when the villagers in those communities are sick, how do they access healthcare? They are even afraid of travelling from one local government to the other for fear of being kidnapped.”

“Therefore, we must be able to address the issue of insecurity,” he said, adding that the health sector is ‘suffering’.

Mr Oche said the high number of children with ‘zero dose’ of essential vaccines and the low immunisation coverage in the region have always been sources of concern for public health practitioners like himself.

Out of curiosity, the public health practitioner said he had taken the samples of some children in a community in Sokoto State to find out if they had taken the BCG vaccine. However, he found that more than 30 per cent of them are not vaccinated against tuberculosis.

“I asked the community leader and he said they’ve only heard of immunisation through the radio, but ‘they don’t come here’,” he said.

Mr Oche added that the challenges that must be overcome to increase immunisation coverage include security, awareness and motivation of health workers who administer the vaccines.

Support PREMIUM TIMES' journalism of integrity and credibility

At Premium Times, we firmly believe in the importance of high-quality journalism. Recognizing that not everyone can afford costly news subscriptions, we are dedicated to delivering meticulously researched, fact-checked news that remains freely accessible to all.

Whether you turn to Premium Times for daily updates, in-depth investigations into pressing national issues, or entertaining trending stories, we value your readership.

It’s essential to acknowledge that news production incurs expenses, and we take pride in never placing our stories behind a prohibitive paywall.

Would you consider supporting us with a modest contribution on a monthly basis to help maintain our commitment to free, accessible news?

TEXT AD: Call Willie - +2348098788999

English (US) ·

English (US) ·